Mohamed Amine Siana

by Jordan Hruska

Originally published in Architectural Record in December 2016

During its 44 years under colonial rule, Morocco served as a petri dish for experiments in modernism by French architects and planners like Jean-François Zevaco and Michel Ecochard. Today, 38-year-old architect Mohamed Amine Siana attempts to reconcile traditional North African architecture with that movement’s imposition on the built environment, in both public and residential buildings. “I try to find a solution to the schizophrenia of our culture in Morocco,” he says. “We are forced to find a language to create a contextual modernism.”

Siana did not intend to become an architect, but his father strongly encouraged him to apply to the National School of Architecture in Rabat, from which he graduated in 2004. For him, the discipline came to represent an expression of culture, people, and sociological behavior. At school, he met classmates Saad El Kabbaj and Driss Kettani, and, over a period of eight years, they pooled resources to work together on the design of three OPEC-funded universities located in Morocco’s tertiary cities of Taroudant, Guelmim, and Laayoune. Each campus comprises a collection of low-rise cubic buildings arrayed around a central axis for the circulation of students and faculty. The schools also share a material palette—distinct rough-hewn ochre cement facades reference the rammed earth used in a medieval city wall at Taroudant, where the architects received their first joint commission.

Limited budgets and the extreme Saharan climate constrained their designs and forced the trio to explore how traditional Berber and Arab architecture contended with desert winds and heat. Research into Arabic medina city planning inspired their inclusion of courtyard gardens typical of the traditional Moroccan house, or riad, within cellular clusters of buildings grouped off the campus’s main axis. To further defend against the sun’s rays, classroom buildings are windowless on the east and west facades. Conversely, courtyard-facing ventilating windows on their north and south facades bring in the gardens’ cooling air. Remarkably, the buildings possess no air-conditioning in a climate that sometimes reaches 118 degrees Fahrenheit. Siana maintains that use of brise-soleils and deeply inset porticos and windows help shield the buildings from sand and sun, and also encourage exploration, creating a sense of mystery through “a vocabulary of hidden spaces.”

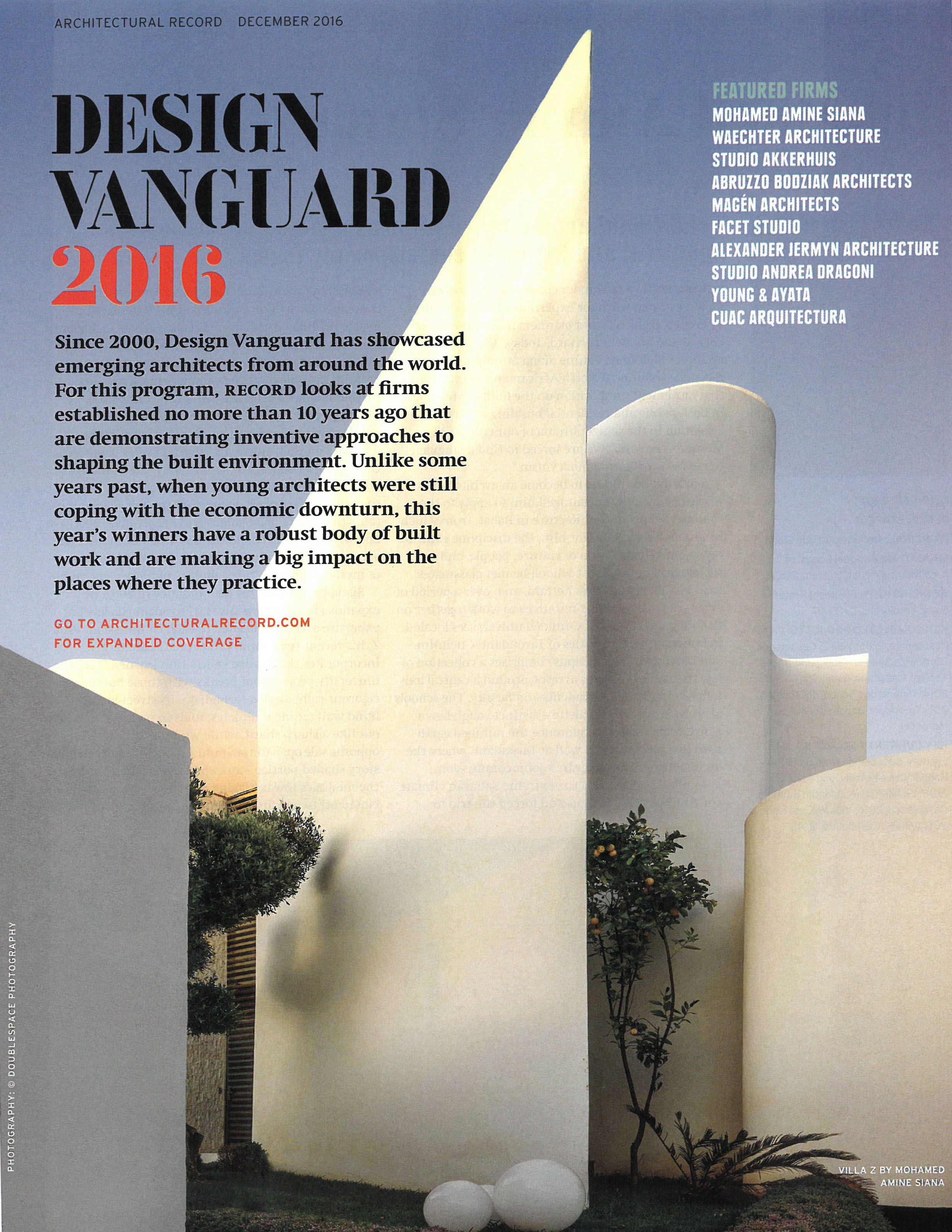

Siana established his own practice in 2007. He expands and contracts his staff to adapt the level of expertise and work needed to each commission. Villa Z, his recent residential project in Casablanca, incorporates the passive ventilation learned from the university projects but breaks with those buildings’ rigorous right-angled formalism. Its street-facing blind wall facade undulates, folds in on itself, and juts out like a sharp shard, while windows on the opposite side open to a swimming pool through a double- story shaded portico—an expressive example of how the medina’s inward-facing logic doesn’t have to be closed off to new interpretations.